“Tuvalu is sinking” is the local catch-all phrase for the effects of climate change on this tiny island archipelago on the frontline of global warming. A Polynesian country situated in Oceania, Tuvalu is no more than a speck in the Pacific ocean, midway between Hawaii and Australia.

The fourth smallest nation in the world, Tuvalu is home to just 11,000 people, most of whom live on the largest island of Fongafale, where they are packed in and fighting for space. Tuvalu’s total land area accounts for less than 26 sq km.

Already, two of Tuvalu’s nine islands are on the verge of going under, the government says, swallowed by sea-rise and coastal erosion. Most of the islands sit barely three metres above sea level, and at its narrowest point, Fongafale stretches just 20m across.

During storms, waves batter the island from the east and the west, “swallowing” the country, in the words of the locals. Many say they have nightmares that the sea will soon gobble them up for good, and not just as a distant fear in their slumber – but by the next generation. Scientists predict Tuvalu could become uninhabitable in the next 50 to 100 years. Locals say they feel it could be much sooner.

Nausaleta Setani, Frank’s aunt, sleeps beside the lagoon at night in the wooden shack, using a float buoy as a pillow. Initially a non-believer in climate change, like many older people on the island, Setani has slowly become convinced of the science as her daily life becomes tougher with every erratic movement of the sea.

- Nausaleta Setani with her nephew in a makeshift structure they use for sleeping, near the Funafuti lagoon

“The weather is changing very quickly, day to day, hour to hour,” says Setani, 54, paradoxically soothed and disturbed by the ocean lapping metres away from her hut.

“I have been learning the things that are happening are the result of man, especially [from] other countries. It makes me sad. But I understand other countries do what is best for their people. I am from a small country. All I want is for the bigger countries to respect us, and think of our lives.”

The United Nations Development Programme classifies Tuvalu as a resource poor, “least-developed country”, that is “extremely vulnerable” to the effects of climate change. Porous, salty soil has made the ground almost totally useless for planting, destroying staple pulaka crops and decreasing the yields of various fruits and vegetables.

Starchy Pacific Island staples such as taro and cassava now have to be imported at great expense, along with most other food.

Since the rising ocean contaminated underwater ground supplies, Tuvalu is now totally reliant on rainwater, and droughts are occurring with alarming frequency. Even if the locals could plant successfully, there is now not enough rain to keep even simple kitchen gardens alive.

- Scenes of Funafuti: a typical home, and freshly caught fish

The Frank family spend around AU$200 (£105) a fortnight on groceries, a bill that keeps rising as the fruit on the trees that ring their modest home – breadfruit, bananas and pandanus – fail to ripen, and fall to the sandy ground, inedible and rotten.

The fish too, the stuff of life here, have become suspect. Ciguatera poisoning affects reef fish who have ingested micro-algaes expelled by bleached coral. When fish infected with these ciguatera toxins are consumed by humans, it causes an immediate and sometimes severe illness: vomiting, fevers and diarrhoea.

At the local hospital, a specialist department has been set up to study and manage climate change-related illnesses.

Around ten Tuvaluans present with ciguatera poisoning every week, accounting for about 10% of the weekly case-load of climate-related illnesses. Suria Eusala Paufolau (left, or above on mobile), acting chief of public health, says cases of fish poisoning began to climb a decade ago; around the same time the weather really started to go haywire.

Climate-related illnesses that have increased on par with the changing weather include influenza, fungal diseases, conjunctivitis, and dengue fever, according to the hospital’s research.

Higher daily temperatures are also putting people at daily risk of dehydration, heatstroke and heat rashes, Paufolau says.

“Generally the local population does not see the link between climate change and health. But there is always a sense of fear about what is happening to our home.”

‘Evacuating is a last resort’

Tuvalu is heavily reliant on foreign aid, with most of its GDP made up from donations from the UN and neighbouring countries.

Education and employment prospects on the island are limited, and the majority of young people whose families can afford it leave to study in Fiji, Australia or New Zealand – a “brain drain” that has been extensively documented.

But as climate change batters the seashore, a trickle of young Tuvaluans are returning, even if coming home can feel claustrophobic after the freedoms of life beyond the islands.

Tapua Pasuna, 24, was crowned Miss Tuvalu last year, and used her platform to campaign for women’s rights and education.

The daughter of the country’s third female MP, Pasuna describes herself as “floating” since she returned from university studies in New Zealand, and says she was drawn back to the island by extensive family obligations, and a sense of responsibility to do what she could for the archipelago.

- Tapua Pasuna, 24, crowned Miss Tuvalu 2018

“I left in 2010. When I came back I immediately noticed the difference. The heat is sometimes unbearable now, and the erosion is also dramatic. Some of my favourite spots have disappeared,” says Pasuna, sitting in a stiff-backed wooden chair in her tropical garden, the barely constructed seawall just metres from her home.

“I feel like this is a part of who I am and I shouldn’t just run away from it, even though it’s disappearing. To just abandon it at such a time as this, when it is hurting – I don’t feel comfortable. I don’t feel like I can do that.”

If this sounds like a tidal wave of despair, the mood on the ground is far less acute. When planes aren’t expected, children ride their bikes and play volleyball on the country’s airstrip, while young courting couples take lazy laps on their motorbikes.

In the afternoons, people snooze in hammocks for hours, and light campfires on the beaches to fry fish and keep the mosquitoes away. A sleepy, sanguine air permeates day-to-day life, as locals watch the lapping of the waves move ever closer.

“Come what may,” locals say again and again, quoting the prime minister, “God will save us.”

The largest building in the capital, Funafuti, is Government House, a three-storey white monolith that houses the offices of the country’s MPs. Tuvalu’s official government policy is to stay on the island – “come what may”.

Plans for adapting to climate change include the ongoing – and much delayed – construction of a sea wall to protect the administrative centre of the capital, funded by the UNDP.

The local town council has a plan to dredge and reclaim land at the south of Fongafale, raise the land 10 metres above sea level, and build high-density housing. It is a plan that would cost US$300m (£233m), and that so far has no funding.

- Fongafale island, home to the Tuvaluan capital, Funafuti

Other options – such as constructing a floating island – are also being explored, as is importing refuse from Australian mines to construct an energy wall to ring the atolls, breaking up the power of the sea as it smashes towards the islands. How the reef ecosystem would survive such a wall has not been explained.

Evacuating the islands is the last resort, says Tuvalu’s prime minister, Enele Sopoaga, despite frequent talk from Pacific neighbours that Tuvaluans will become the world’s first climate-change refugees.

- Enele Sopoaga, prime minister of Tuvalu

Many government officials openly express anger at the election of Donald Trump, saying his climate change scepticism has precipitated a huge step back for global cooperation on climate issues, and made Tuvalu’s small voice on the world stage even smaller.

“I think they hate us,” says Soseala Tinilau (below), the director of the Environment ministry.

Tinilau is referring to the cheerful burning of coal by the US and Australia, among others, despite a recent report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Changewarning that global warming must be kept to a maximum of 1.5C over the next 12 years to avoid catastrophic climate affects.

“During COP [climate] negotiations we had to stay up till 7am to ensure we were listened too,” says Tinilau.

“The world want to ignore us. They want to keep behaving as if we don’t exist, as if what’s happening here isn’t true. We can’t let them.”

Fiji has repeatedly offered land to the Tuvaluan government to relocate their population 1,200km south, an offer the Sopoaga government has not accepted. In a recent essay, former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd suggested Tuvalu’s citizens could be offered full citizenship in exchange for their country’s maritime and fisheries rights; a proposal rejected by Sopoaga as “imperial thinking”.

“Moving outside of Tuvalu will not solve any climate change issues … If you put these people in the middle of industrialised countries it will simply boost their consumptions and increase greenhouse gas emissions,” says Sopoaga, a fierce advocate for global cooperation on climate change issues.

“I am very worried about this very self-defeatist approach to suggest that people from low-lying, at-risk countries could be relocated. Because it fails to understand the implications of this issue for the entire world.”

Sopoaga says there is “no plan B” for Tuvalu, and every government effort is concentrated on adapting to the changing weather patterns – and staying put.

“We cannot just say, ‘Kick these people out.’ It is too simplistic and defeatist an approach,” says Sopoaga.

“I think it would be a great shame for the world to allow that to happen. I believe we still have time to make this island very attractive, very beautiful, and continue to be inhabited by generations of Tuvaluans to come.”

Seen from the air, Tuvalu looks like paradise: a slim scar of sand densely planted with coconut palms, and ringed by shallow emerald waters. But up close, the fragility of the land reveals itself. Beside the runway, golden sand spills on to the concrete, and scraggly green grass struggles to survive. The horizon is flat, and dominated by sea; sea that presses at you from every side. The air – ripe, over-cooked – pushes people into the dark interiors of their homes in the middle of the day, sticky and cloying.

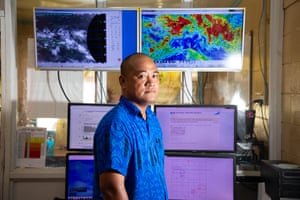

At Tuvalu’s Bureau of Meteorology, situated on the edge of the runway – with pig pens to its left and the country’s prison to its right (home to just six inmates) – Nikotemo Iona and his small team are working overtime as they crunch the latest rainfall measurements. They are hours away from declaring another drought.

- Nikotemo Iona at the Bureau of Meteorology

According to local climate data, Iona says the biggest impacts of climate change on Tuvalu have been rising air temperatures, more intense and frequent storm surges and decreasing rainfall, as well as the total inundation of low-lying coastal parts of Funafuti – including, sometimes, the country’s lifeline, its runway.

“Many people intend to migrate in response to climate change,” says Iona, sitting inside his squat, concrete office, designed to stay upright and continue broadcasting during cyclone season, which is intensifying year on year.

“However, most of the older generation do not want to move as they believe the will lose their identity, culture, lifestyle and traditions. But I believe that younger generations intend to migrate for the sake of the future generations.”

During storm surges or the highest tides, the Pacific Ocean bubbles up from the sandy soil under Enna Sione’s small yellow house. Fifty metres away, palm trees lie scattered across a rocky, coral strewn beach, turning grey in the hot sun, their twisted, decaying root systems facing skywards.

- Enna Sione, next to the ocean that frequently floods her home

Sitting on a slayed coconut tree, Sione’s eyes are troubled as she stares at the ocean, beating its relentless path against her home. Sione, her husband and four children are planning to migrate to New Zealand in the next two years – to join more than 2,000 of fellow Tuvaluans already resident in the country; a migrant population that doubles every five years.

“The weather has really, extremely changed. Sometimes I feel scared of the ocean,” says Sione, who adds that she is leaving for the sake of her kids.

“Maybe one time Tuvalu will disappear. From what I can see a lot is already gone. I think one day we will disappear.”